When we were asked to work with Mufti Games, a Bristol-based organisation which creates playful and memorable experiences for all ages, naturally we jumped at the chance. There is overwhelming evidence of the importance of play in learning, you only have to look at the work of Semour Papert and Mitch Resnik and ultimately their involement in the development of the Lifelong Kindergarten at MIT to see how play is central to understanding the nature of play. As we shared a common goal to help people feel more comfortable about inventing through play, it seemed that a workshop where both the STEAMShip and Mufti Games could share ideas about how to get young people involved in tinkering and constructing, was a fitting way to work together.

To prepare for the workshop, I visited Malcolm at an earlier Mufti Games workshop, a few weeks before our workshop to see how he used his approach to play. The workshop was being run at Hop, Skip and Jump, near Bristol for the Centre for Adoption Support and Education as an open sessions to allow some chance for potential adopters to meet with parents of adopted children, but also for the children themselves to meet others and play in a supportive and very creative environment. Often children who have experiences early-life trauma can have quite profound and long term issues which make it difficult for them to form attachments to their parents and other adults in their support network. So its very important that play forms part of the way that they learn to develop their self-esteem.

On the day of this earlier workshop, Malcolm turned up with a sound machine cart with lots of junk bolted all over and a chalk board attached to write down ideas. There appeared at first to be no preconceived plans as to what would happen, for that, it would first need some willing participants.

There were some adult volunteers on hand who were able to help and encourage the children interact with the sound machine. As time went on it became clear that Malcolm suggested some instructions. He was very subtly attempting to gamify the experience of interaction with the sound machine. By encouraging signalling, the children could be given some tools to construct a game around the experience. They took it in another direction themselves. By moving the cart, around the playground it became a sort of procession and as a result a performance. This was totally unexpected but the atmosphere became more energetic. The game was not a formal game of rules but an open-ended playful experience.

It reminded me of an approach to self-organised learning taken by Sugata Mitra in his groundbreaking experiments in remote indian villages, (see https://www.edutopia.org/blog/self-organized-learning-sugata-mitra) where children who had never previously had access to the internet, were nonetheless interacting with it and searching the internet in an unfamiliar language after just a few hours. At the STEAMShip we are continually reevaluating our approach to the learning experience and exploring some of these approaches to develop open-ended learning to support innovation and invention through STEAM practice.

The day came for our collaborative workshop. We had built up a collection of electronic junk to take apart. I tried to predict what would be needed for this workshop and brought a bit of everything I had, lots of motors and components and different micro controllers and a laptop. Malcolm also brought lots of electronic junk so we had lots of different things to take apart.

When I arrived, we setup and there were a number of helpers on hand to help children with some of the more difficult tasks of taking things apart and to be present should any sharp objects be uncovered in the process. These were a mixture of parents, volunteer helpers and Alice Haynes from KWMC (Knowle West Media Centre) who has a special interest in soft robotics. It was very interesting to be involved with this workshop where we were all coming to the workshop from slightly different perspectives.

As the children arrived they very confidently took apart anything and everything. Unlike teenagers, who I have found from experience, are sometimes a little more cautious about taking things apart and need permission. Younger children don’t have the same fear or inhibitions about dismantling objects, some in fact take complete delight in destroying objects.

I watched for some interesting components to be revealed so that I could hook up some of them to a BBC Micro:bit I had brought with me.

So I was able to get this making musical tones to encourage some of the children in applying blocks of code to speakers so that they could see how their actions would change the results of their tinkering.

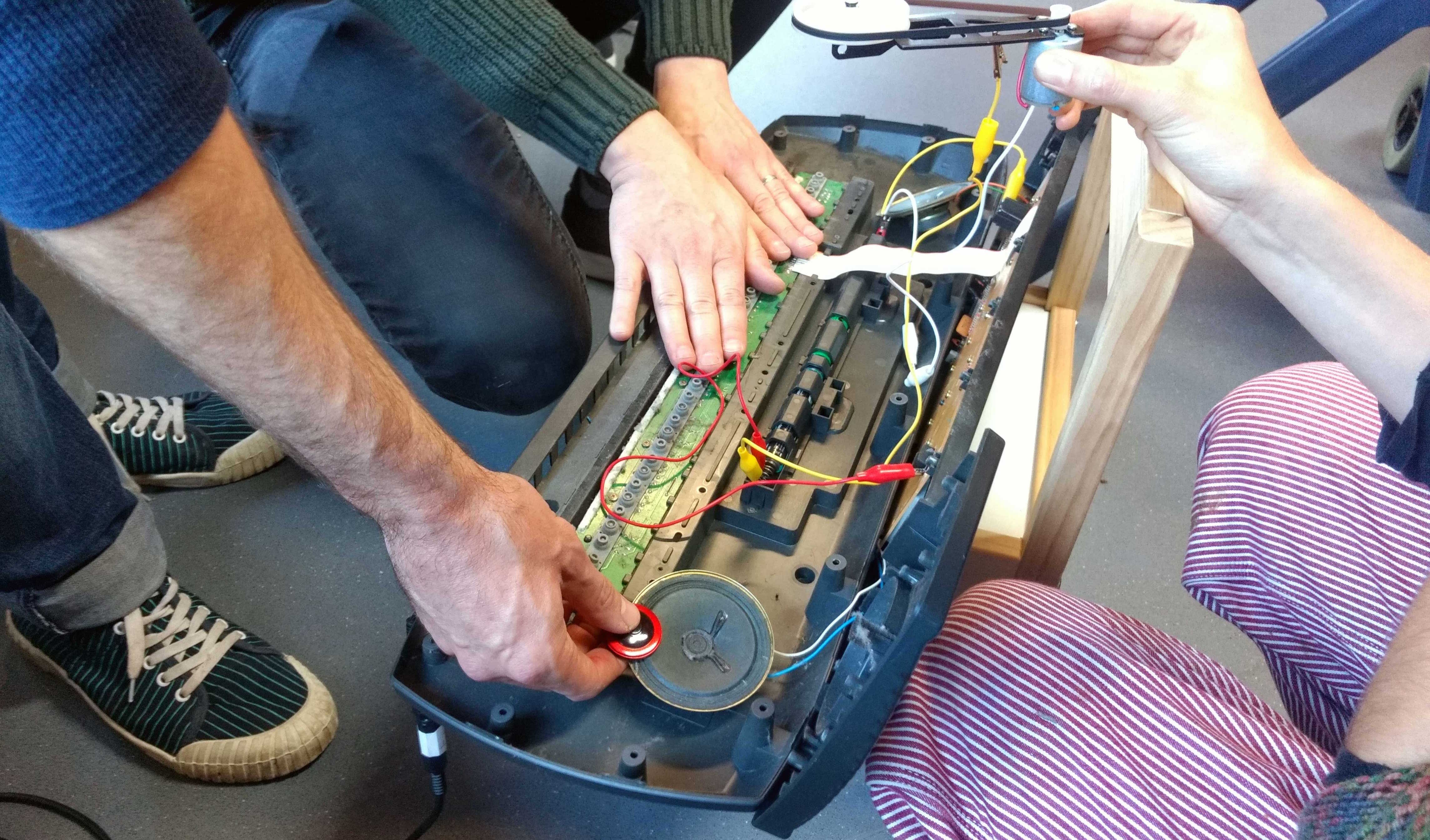

At the same time Malcolm and Alice were trying to “circuit-bend” a partially dismantled keyboard. I had also brought some contact piezo microphones with me as I wanted to create something I had previously seen working well at the Exploratorium. At a certain point we tried to bring the microphone to the circuit-bent keyboard to try and amplify the sound of the speaker but it soon became clear that it was much more fun to amplify a motor that one of the children had been hooking up.

These “lightbulb” moments were many during this workshop and despite the lack of structure, real learning was taking place. Even though some participants only stayed for a few minutes, it was interesting to see that they returned, but also how involved their parents or guardians were in the process of dismantling and tinkering with the junk. What was most interesting though was how the children were fearless dismantlers and also how they were constantly asking what comes next. Some of their prototype ideas were built by them coming back to the workshop two or three times. Their “growth mindset” approach is a natural part of their playful experience at this age, sometimes they were offering solutions to what could happen next. Like Sugata Mitra’s observations in the remote villages in India, sometimes an adult helper is needed to offer a suggestion to move things forward, but if the adults get too involved, the children tend to either lose interest or get frustrated. I have found that often as they go through school and the pressure of exams take over their daily routine, their natural sense of play and wonderment disappears. In some children, if they are lucky, this remains right through to adulthood but for many it is lost and it is sometimes difficult to rekindle. At the STEAMShip we are striving to build tools and experiences that give people toolboxes to enable them to play. Sometimes this involves technology but sometimes it can just involve more mundane materials which when combined can create new and inventive “toys” but they can even lead to much deeper learning experiences too.

After the workshop, I had an opportunity to catch up with Malcolm at the Pervasive Media Studio where he was doing a talk on the ethos of Mufti Games in which he talked about how people at different ages need permission to play. From his experience, people are not conditioned to play once they have gone through the routine of school and start their adult life and for most, start their working life. If given permission to play, they are transported back their childhood, and begin to play without being too self-conscious, like they were back in kindergarten or pre-school. In his talk he challenged the audience to find ways to play in their own environment by deviating from their normal routine and this is a challenge we are definitely ready to accept.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.